Here is our free GED Language Arts practice test. These practice questions will help you prepare for the Reasoning Through Language Arts test. You will be given a total of 150 minutes for this section of the GED. The first part of this test has 51 multiple choice questions that must be answered within 95 minutes. This is followed by a 10 minute break and then a 45 minute essay question. Start practicing right now with our GED Language Arts test questions.

0 of 43 Questions completed

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading…

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You must first complete the following:

0 of 43 Questions answered correctly

Time has elapsed

You have reached 0 of 0 point(s), ( 0 )

Earned Point(s): 0 of 0 , ( 0 )

0 Essay(s) Pending (Possible Point(s): 0 )

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box.

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

The History of Girl Scout Cookies

For nearly 100 years, the Girl Scouts and their supporters have made their annual cookie sale into an iconic American tradition—and all while they learned valuable life lessons, made their communities better, and most of all: had fun.

Girl Scout Cookies began long ago in the kitchens of troop members, with moms volunteering to help advise. In 1917, only 5 years after the Girl Scouts of America was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, the Mistletoe Troop in Muskogee, Oklahoma began baking and selling cookies in their high school cafeteria as a service project. From these humble beginnings, a national fundraising phenomenon was born.

By 1922, the Girls Scouts of America were getting the word out about this amazing fundraiser. The American Girl magazine (published by GSA), featured an article by Florence E. Neill, a local director in Chicago, Illinois, which provided a cookie recipe complete with a sales plan. In 1933, the Greater Philadelphia Council began baking cookies and selling them in city’s gas and electric company windows in 1933. Local Girl Scout troops raised money and developed marketing and business skills. By 1934, they became the first council to sell commercially baked cookies.

The Girl Scout Federation of Greater New York soon followed Philadelphia’s lead in 1935, but they added the words “Girl Scout Cookies” to their box. Within a year, the national Girl Scout organization had realized the potential shown in these cities, and began licensing the production of cookies to be sold nationwide. The national excitement for Girl Scout cookies built from there, and by 1951 Girl Scout cookies came in three varieties: Sandwich, Shortbread, and Chocolate Mints. By the 1970’s, the GSA was selling 8 different varieties of cookies.

In more recent years, the GSA has begun to focus more heavily on design, bold and bright boxes that captured the spirit of Girl Scouting. There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

There are still 8 varieties of cookies, but now they’re kosher and, much to the excitement of our youngest Girl Scouts, Daisies started selling cookies!

From: Jill Peterson, Senior Vice President

Date: April 19, 2016

Subject: Strategic Changes and Welcome Luncheon

As you are all aware, we will be transitioning from our existing client management system to a new platform which includes more advanced analytics capabilities. This change will help us to match our [8] ———— with more appropriate products. In addition to this improved product selection, the new customer management system will provide a more uniform data management platform across departments.

Another issue I will like to bring to your attention involves the introduction of our 24-hour customer support line. We will need to run a third shift from 12:00 AM – 8:00 AM to staff the 24-hour customer support line and would like to invite interested employees to contact [9] ————————— their interest in working on the third shift. Third shift employees will be paid overtime rates, which should serve as additional motivation for those looking to make some extra cash.

Finally, Robin Messer will be joining our company next week as head of our commercial lending division. Robin has been working at Affinity Bank for the past 5 years where she increased [10] ———— commercial lending portfolio by 80 percent over that time. Her previous experience [11] ———— stints with JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs. We will be holding a public luncheon on April 29, 2016 to formally welcome her into the fold.

From: Jill Peterson, Senior Vice President

Date: April 19, 2016

Subject: Strategic Changes and Welcome Luncheon

As you are all aware, we will be transitioning from our existing client management system to a new platform which includes more advanced analytics capabilities. This change will help us to match our [8] ———— with more appropriate products. In addition to this improved product selection, the new customer management system will provide a more uniform data management platform across departments.

Another issue I will like to bring to your attention involves the introduction of our 24-hour customer support line. We will need to run a third shift from 12:00 AM – 8:00 AM to staff the 24-hour customer support line and would like to invite interested employees to contact [9] ————————— their interest in working on the third shift. Third shift employees will be paid overtime rates, which should serve as additional motivation for those looking to make some extra cash.

Finally, Robin Messer will be joining our company next week as head of our commercial lending division. Robin has been working at Affinity Bank for the past 5 years where she increased [10] ———— commercial lending portfolio by 80 percent over that time. Her previous experience [11] ———— stints with JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs. We will be holding a public luncheon on April 29, 2016 to formally welcome her into the fold.

From: Jill Peterson, Senior Vice President

Date: April 19, 2016

Subject: Strategic Changes and Welcome Luncheon

As you are all aware, we will be transitioning from our existing client management system to a new platform which includes more advanced analytics capabilities. This change will help us to match our [8] ———— with more appropriate products. In addition to this improved product selection, the new customer management system will provide a more uniform data management platform across departments.

Another issue I will like to bring to your attention involves the introduction of our 24-hour customer support line. We will need to run a third shift from 12:00 AM – 8:00 AM to staff the 24-hour customer support line and would like to invite interested employees to contact [9] ————————— their interest in working on the third shift. Third shift employees will be paid overtime rates, which should serve as additional motivation for those looking to make some extra cash.

Finally, Robin Messer will be joining our company next week as head of our commercial lending division. Robin has been working at Affinity Bank for the past 5 years where she increased [10] ———— commercial lending portfolio by 80 percent over that time. Her previous experience [11] ———— stints with JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs. We will be holding a public luncheon on April 29, 2016 to formally welcome her into the fold.

From: Jill Peterson, Senior Vice President

Date: April 19, 2016

Subject: Strategic Changes and Welcome Luncheon

As you are all aware, we will be transitioning from our existing client management system to a new platform which includes more advanced analytics capabilities. This change will help us to match our [8] ———— with more appropriate products. In addition to this improved product selection, the new customer management system will provide a more uniform data management platform across departments.

Another issue I will like to bring to your attention involves the introduction of our 24-hour customer support line. We will need to run a third shift from 12:00 AM – 8:00 AM to staff the 24-hour customer support line and would like to invite interested employees to contact [9] ————————— their interest in working on the third shift. Third shift employees will be paid overtime rates, which should serve as additional motivation for those looking to make some extra cash.

Finally, Robin Messer will be joining our company next week as head of our commercial lending division. Robin has been working at Affinity Bank for the past 5 years where she increased [10] ———— commercial lending portfolio by 80 percent over that time. Her previous experience [11] ———— stints with JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs. We will be holding a public luncheon on April 29, 2016 to formally welcome her into the fold.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

Getting Started with Yoga

There are many styles of yoga taught in the west. Some styles emphasize power and are physically challenging, while others are more meditative in nature. The style you choose should be based on why you want to do yoga in the first place. Many students start yoga simply for the value of a balanced exercise, since there is equal emphasis on strength and flexibility. After a while, they may discover that they become interested in other aspects of the practice, such as pranayama, or breathing techniques, which can be excellent for relaxation.

Once you’ve decided which style you want to study, you have to find a class. Some students just choose a studio that is easy to get to, or has free parking. But even if you do this, there will probably be several teachers offering classes. It can be tricky to find the right teacher.

Yoga teachers can become certified by taking a course, although there is no standardized certification implemented by any state or by the federal government. Where certification does exist, it can be for courses that last as little as a weekend or as long as a year, or even more. As a result, many places that offer yoga classes do not require their teachers to have any particular training, and if they do, students may not know exactly what the certification reflects.

So how does a student select a good teacher? Word-of-mouth referrals are always good. Students can also try a class to decide if that teacher is a good fit. In the end, the choice of a teacher has many different facets, not all of which will be as important to all students. What works well for you might not work well for your best friend. In addition, as you grow as a yoga student, you may find you need to change your teacher too.

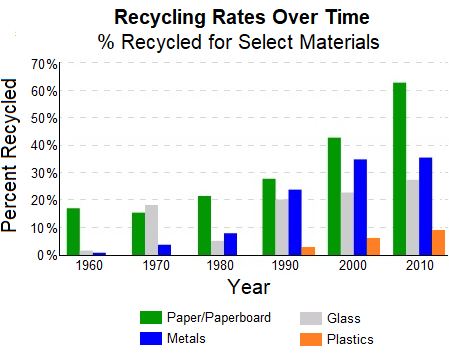

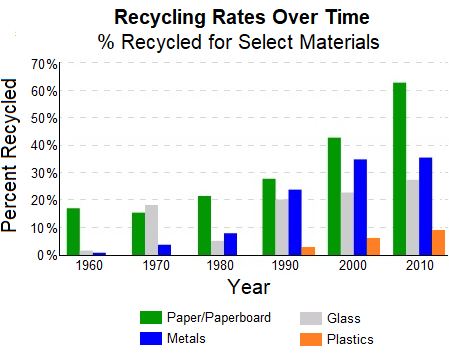

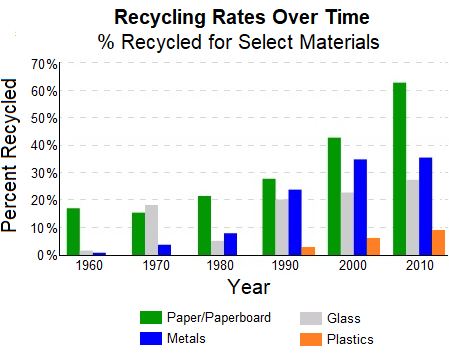

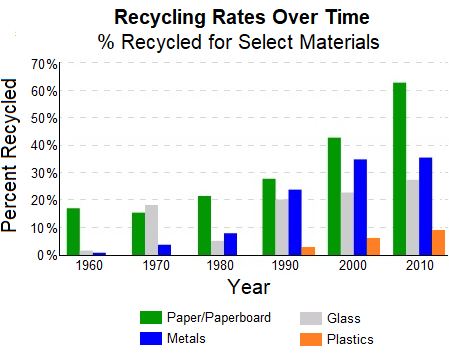

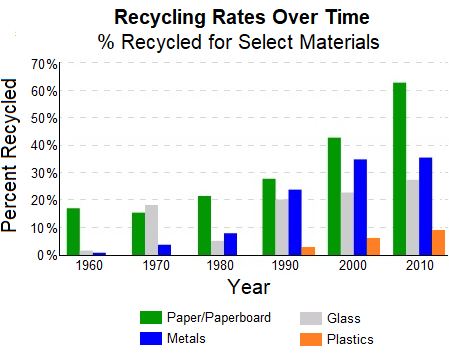

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

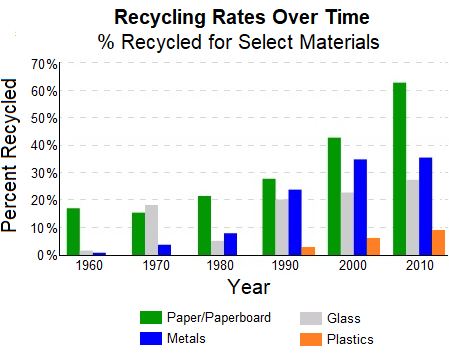

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

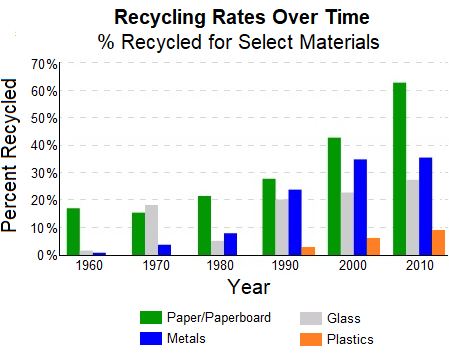

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

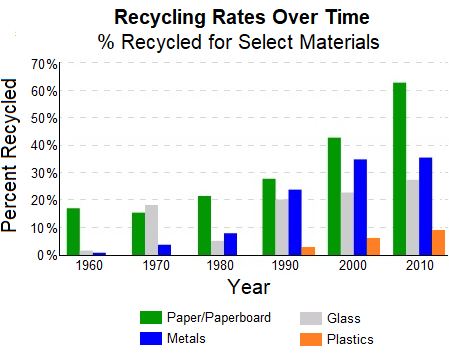

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

Recycling Facts

Whether it’s saving milk jugs, sorting newspapers neatly into a pile or placing unnecessary office paper in a corner recycling bin, the American recycling experiment continues. Consider the set of recycling statistics, reflected in the bar chart. It compares American recycling rates for select materials (paper, glass, metals and plastics) over a fifty year time frame (1960–2010), using ten year intervals.

The large green bars on the graph show that between 1960 and 2010, paper recycling rates exceeded the recycling rates for the other materials. As the years pass, American recycling habits expanded, with beverage container recycling explaining much of the increase in glass, metals and plastics recycling in 1990. Starting in 1990, yard trimming recycling rates, not presented in the top bar chart, also occupied a larger portion of the average American’s recycling efforts. By 2010, Americans were recycling 57.5% of all their yard trimmings.

In many locations, changing technology and community practices contributed to recycling rate upward momentum over this same sixty year time frame. Reverse vending machines, invented during a 1990s recycling technology wave, now fill space in many retail locations around the country. State beverage container recycling laws and ease of use account for a portion of their long term success.

While circumstances exist where individuals might need a moment to stop and think through any particular recycling task, most modern recycling tasks, like using reverse vending machines, are quite simple, and accomplished by many individuals unreflective participation in organized beverage container recycling programs.

Creating a successful home, school, or work recycling program takes very little effort, while creating substantial environmental and economic benefits. Recycling practices easily blend into modern American life. Most successful recycling programs begin and end with locating their recycling corner. Strategically placing a recycling center in a corner of a high traffic location often works to attract individual attention along with providing a centralized waste removal location.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a women’s rights activist and a leader in the movement that eventually secured American women the right to vote. Her early education, upbringing, and interest in social matters set her on a path of leadership, and she inspired other men and women to take up the cause as well.

Unlike other activists such as Susan B. Anthony, who was clearly focused on the issue of voting rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wanted to promote the broader issue of women’s rights and address issues such as women’s custody and property rights, employment and income rights, divorce laws, birth control, and abortion. Even though Anthony and Stanton disagreed on the focus of the women’s rights movement, they remained friends and continued working together towards voting rights for women.

Stanton remained focused on her work, writing many important books, documents, and speeches for the women’s rights movement. She also traveled and lectured widely, earning money to pay for her sons to attend college. Stanton promoted voting rights for women in several states, and she made an unsuccessful attempt to secure a U.S. Congressional seat from New York.

As Stanton grew older, she became more active internationally, and in 1888, she worked to found the International Council of Women. In the U.S., it took until 1890 for the divided supporters of the women’s rights movement to eventually reunite as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Stanton became the organization’s first president. After spending over five decades working towards equal rights for women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902, still some twenty years before women gained the right to vote.

Because of her controversial ideas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was initially overshadowed by Susan B. Anthony, who was more often recognized as the founder of the women’s rights movement. Over time, however, formal recognition of Stanton’s work has increased. Today, Elizabeth Cady Stanton is rightly acknowledged for taking a founding role in the movement that secured voting rights for women and for shaping the broader movement towards more equal rights for women in society at large.

Mr. Eric Nielsen

Chief Executive Officer

Swirl Corporation

Wilmington, NC 28409 Dear Mr. Nielsen: [32] ———- have been loyal customers of the Swirl Corporation for the past 30 years. We have purchased various household appliances such as dishwashers, ovens, washers, and dryers from the local Swirl outlet store since moving here in the early nineties. We recently purchased a Swirl Eco Energy Star refrigerator from your store to replace our old non-Energy Star refrigerator. The new refrigerator worked well for two months before the top freezer stopped cooling completely. Our energy bills also seem to have increased by about $25/month since we bought this new Energy Star model. Upon researching the problem, I found that there have been recalls of several products with serial numbers [33] ————–. I spoke to [34] ————– at the outlet store, but all he did was tell me to call your toll free number. Upon calling the toll free number, I was told I to return the refrigerator to the outlet store for forwarding to your distribution facility. It has been three weeks since we returned the refrigerator to your [35] —————– a status update on the refrigerator. Our energy bills have dropped back to their original level since we switched back to our old refrigerator. However, our goal was to reduce our energy bill, so we are still dissatisfied. If you would like to retain us as customers, then please address these issues immediately. Sincerely, Horace Whittaker III

Mr. Eric Nielsen

Chief Executive Officer

Swirl Corporation

Wilmington, NC 28409 Dear Mr. Nielsen: [32] ———- have been loyal customers of the Swirl Corporation for the past 30 years. We have purchased various household appliances such as dishwashers, ovens, washers, and dryers from the local Swirl outlet store since moving here in the early nineties. We recently purchased a Swirl Eco Energy Star refrigerator from your store to replace our old non-Energy Star refrigerator. The new refrigerator worked well for two months before the top freezer stopped cooling completely. Our energy bills also seem to have increased by about $25/month since we bought this new Energy Star model. Upon researching the problem, I found that there have been recalls of several products with serial numbers [33] ————–. I spoke to [34] ————– at the outlet store, but all he did was tell me to call your toll free number. Upon calling the toll free number, I was told I to return the refrigerator to the outlet store for forwarding to your distribution facility. It has been three weeks since we returned the refrigerator to your [35] —————– a status update on the refrigerator. Our energy bills have dropped back to their original level since we switched back to our old refrigerator. However, our goal was to reduce our energy bill, so we are still dissatisfied. If you would like to retain us as customers, then please address these issues immediately. Sincerely, Horace Whittaker III

Mr. Eric Nielsen

Chief Executive Officer

Swirl Corporation

Wilmington, NC 28409 Dear Mr. Nielsen: [32] ———- have been loyal customers of the Swirl Corporation for the past 30 years. We have purchased various household appliances such as dishwashers, ovens, washers, and dryers from the local Swirl outlet store since moving here in the early nineties. We recently purchased a Swirl Eco Energy Star refrigerator from your store to replace our old non-Energy Star refrigerator. The new refrigerator worked well for two months before the top freezer stopped cooling completely. Our energy bills also seem to have increased by about $25/month since we bought this new Energy Star model. Upon researching the problem, I found that there have been recalls of several products with serial numbers [33] ————–. I spoke to [34] ————– at the outlet store, but all he did was tell me to call your toll free number. Upon calling the toll free number, I was told I to return the refrigerator to the outlet store for forwarding to your distribution facility. It has been three weeks since we returned the refrigerator to your [35] —————– a status update on the refrigerator. Our energy bills have dropped back to their original level since we switched back to our old refrigerator. However, our goal was to reduce our energy bill, so we are still dissatisfied. If you would like to retain us as customers, then please address these issues immediately. Sincerely, Horace Whittaker III

Mr. Eric Nielsen

Chief Executive Officer

Swirl Corporation

Wilmington, NC 28409 Dear Mr. Nielsen: [32] ———- have been loyal customers of the Swirl Corporation for the past 30 years. We have purchased various household appliances such as dishwashers, ovens, washers, and dryers from the local Swirl outlet store since moving here in the early nineties. We recently purchased a Swirl Eco Energy Star refrigerator from your store to replace our old non-Energy Star refrigerator. The new refrigerator worked well for two months before the top freezer stopped cooling completely. Our energy bills also seem to have increased by about $25/month since we bought this new Energy Star model. Upon researching the problem, I found that there have been recalls of several products with serial numbers [33] ————–. I spoke to [34] ————– at the outlet store, but all he did was tell me to call your toll free number. Upon calling the toll free number, I was told I to return the refrigerator to the outlet store for forwarding to your distribution facility. It has been three weeks since we returned the refrigerator to your [35] —————– a status update on the refrigerator. Our energy bills have dropped back to their original level since we switched back to our old refrigerator. However, our goal was to reduce our energy bill, so we are still dissatisfied. If you would like to retain us as customers, then please address these issues immediately. Sincerely, Horace Whittaker III

The Civil War Crisis The fall of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, did not produce the Civil War crisis. In 1858, Lincoln had forewarned the country in his “House Divided” speech. Early in February of 1860, Jefferson Davis, on behalf of the South, had introduced his famous resolutions in the Senate. This document was the ultimatum of the dissatisfied slave-holding commonwealths. It demanded that Congress should protect slavery throughout the domain of the United States. The territories, it declared, were the common property of the states of the Union and hence open to the citizens of all states with all their personal possessions. The Northern states, furthermore, were no longer to interfere with the working of the Fugitive Slave Act. They must respect the Dred Scott decision of the Federal Supreme Court. Dred Scott, a slave who had lived in the free state of Illinois and the free territory of Wisconsin before moving back to the slave state of Missouri, had appealed to the Supreme Court in hopes of being granted his freedom. The decision of the court was read in March of 1857. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney — a staunch supporter of slavery — wrote the “majority opinion” for the court. It stated that because Scott was black, he was not a citizen and therefore had no right to sue. The decision also declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820, legislation which restricted slavery in certain territories, unconstitutional. Neither in their own legislatures nor in Congress could the Northern states trespass upon the right of the South to regulate slavery as it best saw fit. These resolutions, demanding in effect that slavery be thus safeguarded — almost to the extent of introducing it into the free states — really foreshadowed the Democratic platform of 1860 which led to the great split in that party, the victory of the Republicans under Lincoln, the subsequent secession of the more radical southern states, and finally the Civil War, for it was inevitable that the North, when once aroused, would bitterly resent such pro-slavery demands. And this great crisis was only the bursting into flame of many smaller fires that had long been smoldering. For generations the two sections had been drifting apart. Since the middle of the seventeenth century, Mason and Dixon’s line had been a line of real division separating two inherently distinct portions of the country. Naturally, the conflict would at once present intricate military problems, and among them the retention of the Pacific Coast was of the deepest concern to the Union. Situated at a distance of nearly two thousand miles from the Missouri river which was then the nation’s western frontier, this intervening space comprised trackless plains, almost impenetrable ranges of snow-capped mountains, and parched alkali deserts. And besides these barriers of nature which lay between the West coast and the settled eastern half of the country, there were many fierce tribes who were usually on the alert to oppose the movements of the white race through their dominions. Adapted from “The Story of the Pony Express” by Glenn D. Bradley.

The Civil War Crisis

The fall of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, did not produce the Civil War crisis. In 1858, Lincoln had forewarned the country in his “House Divided” speech. Early in February of 1860, Jefferson Davis, on behalf of the South, had introduced his famous resolutions in the Senate. This document was the ultimatum of the dissatisfied slave-holding commonwealths. It demanded that Congress should protect slavery throughout the domain of the United States. The territories, it declared, were the common property of the states of the Union and hence open to the citizens of all states with all their personal possessions. The Northern states, furthermore, were no longer to interfere with the working of the Fugitive Slave Act. They must respect the Dred Scott decision of the Federal Supreme Court.

Dred Scott, a slave who had lived in the free state of Illinois and the free territory of Wisconsin before moving back to the slave state of Missouri, had appealed to the Supreme Court in hopes of being granted his freedom. The decision of the court was read in March of 1857. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney — a staunch supporter of slavery — wrote the “majority opinion” for the court. It stated that because Scott was black, he was not a citizen and therefore had no right to sue. The decision also declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820, legislation which restricted slavery in certain territories, unconstitutional.

Neither in their own legislatures nor in Congress could the Northern states trespass upon the right of the South to regulate slavery as it best saw fit. These resolutions, demanding in effect that slavery be thus safeguarded — almost to the extent of introducing it into the free states — really foreshadowed the Democratic platform of 1860 which led to the great split in that party, the victory of the Republicans under Lincoln, the subsequent secession of the more radical southern states, and finally the Civil War, for it was inevitable that the North, when once aroused, would bitterly resent such pro-slavery demands. And this great crisis was only the bursting into flame of many smaller fires that had long been smoldering. For generations the two sections had been drifting apart. Since the middle of the seventeenth century, Mason and Dixon’s line had been a line of real division separating two inherently distinct portions of the country.

Naturally, the conflict would at once present intricate military problems, and among them the retention of the Pacific Coast was of the deepest concern to the Union. Situated at a distance of nearly two thousand miles from the Missouri river which was then the nation’s western frontier, this intervening space comprised trackless plains, almost impenetrable ranges of snow-capped mountains, and parched alkali deserts. And besides these barriers of nature which lay between the West coast and the settled eastern half of the country, there were many fierce tribes who were usually on the alert to oppose the movements of the white race through their dominions.

Adapted from “The Story of the Pony Express” by Glenn D. Bradley.

The Civil War Crisis The fall of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, did not produce the Civil War crisis. In 1858, Lincoln had forewarned the country in his “House Divided” speech. Early in February of 1860, Jefferson Davis, on behalf of the South, had introduced his famous resolutions in the Senate. This document was the ultimatum of the dissatisfied slave-holding commonwealths. It demanded that Congress should protect slavery throughout the domain of the United States. The territories, it declared, were the common property of the states of the Union and hence open to the citizens of all states with all their personal possessions. The Northern states, furthermore, were no longer to interfere with the working of the Fugitive Slave Act. They must respect the Dred Scott decision of the Federal Supreme Court. Dred Scott, a slave who had lived in the free state of Illinois and the free territory of Wisconsin before moving back to the slave state of Missouri, had appealed to the Supreme Court in hopes of being granted his freedom. The decision of the court was read in March of 1857. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney — a staunch supporter of slavery — wrote the “majority opinion” for the court. It stated that because Scott was black, he was not a citizen and therefore had no right to sue. The decision also declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820, legislation which restricted slavery in certain territories, unconstitutional. Neither in their own legislatures nor in Congress could the Northern states trespass upon the right of the South to regulate slavery as it best saw fit. These resolutions, demanding in effect that slavery be thus safeguarded — almost to the extent of introducing it into the free states — really foreshadowed the Democratic platform of 1860 which led to the great split in that party, the victory of the Republicans under Lincoln, the subsequent secession of the more radical southern states, and finally the Civil War, for it was inevitable that the North, when once aroused, would bitterly resent such pro-slavery demands. And this great crisis was only the bursting into flame of many smaller fires that had long been smoldering. For generations the two sections had been drifting apart. Since the middle of the seventeenth century, Mason and Dixon’s line had been a line of real division separating two inherently distinct portions of the country. Naturally, the conflict would at once present intricate military problems, and among them the retention of the Pacific Coast was of the deepest concern to the Union. Situated at a distance of nearly two thousand miles from the Missouri river which was then the nation’s western frontier, this intervening space comprised trackless plains, almost impenetrable ranges of snow-capped mountains, and parched alkali deserts. And besides these barriers of nature which lay between the West coast and the settled eastern half of the country, there were many fierce tribes who were usually on the alert to oppose the movements of the white race through their dominions. Adapted from “The Story of the Pony Express” by Glenn D. Bradley.